Side Effect Onset Calculator

How soon after starting medication do side effects typically appear?

Enter your drug class and symptom to see the typical time-to-onset window.

Why Some Side Effects Hit Fast and Others Take Months

You start a new medication. A week later, your muscles ache. Or maybe it’s day three and your throat swells. Or it’s six months in - and you finally realize your weird dizziness isn’t just stress. Time-to-onset isn’t just a medical term - it’s the clock that tells you whether your symptoms are from the drug or something else entirely.

Most people assume side effects show up right away. But that’s not true. Some hit within hours. Others creep in slowly, hiding behind other health issues. Knowing when to expect trouble isn’t just helpful - it can save your life.

Fast Triggers: Hours to Days

Some drugs don’t mess around. If you’re on an ACE inhibitor like lisinopril or enalapril and you suddenly get swelling in your lips, tongue, or throat - that’s angioedema. For histamine-driven cases, it’s usually within minutes to hours. But here’s the twist: the kind caused by ACE inhibitors? It can wait. One study found it could pop up anywhere from the first week to six months later. That’s why doctors miss it. Patients don’t connect the dots because they’ve been on the drug for months.

Antibiotics like ciprofloxacin are another fast actor. Peripheral nerve pain - that burning, tingling feeling in your hands or feet - shows up in just two days on average. Women get it even faster than men. And if you’re taking statins? Muscle pain might seem like it’s from the drug, but research shows it’s just as likely to happen with a placebo. The real trigger? Stopping the pill. In one trial, over half of patients felt better within three days - whether they were on the real drug or sugar pills. That’s the nocebo effect in action: your brain expects pain, so it finds it.

Weeks to a Month: The Silent Buildup

Not all reactions scream for attention. Some whisper. Pregabalin and gabapentin - used for nerve pain and seizures - often cause dizziness or fatigue. In patient reviews, more than half reported these symptoms within the first week. But the median time? 19 and 31 days respectively. That’s a gap between expectation and reality. You start the drug, feel fine for two weeks, then think, “Why am I so tired?” You blame sleep, stress, aging. It’s not until you stop and the fog lifts that you realize it was the medication.

Drug-induced liver injury follows a similar pattern. With most drugs, it takes about six weeks. But acetaminophen? That’s different. Too much in one go, and your liver starts failing within 24 hours. That’s direct toxicity. Other drugs? It’s your body’s immune system slowly turning on the drug. That’s why doctors check liver enzymes after four to six weeks of starting a new medication - it’s not random. It’s science.

Months to a Year: The Delayed Bombs

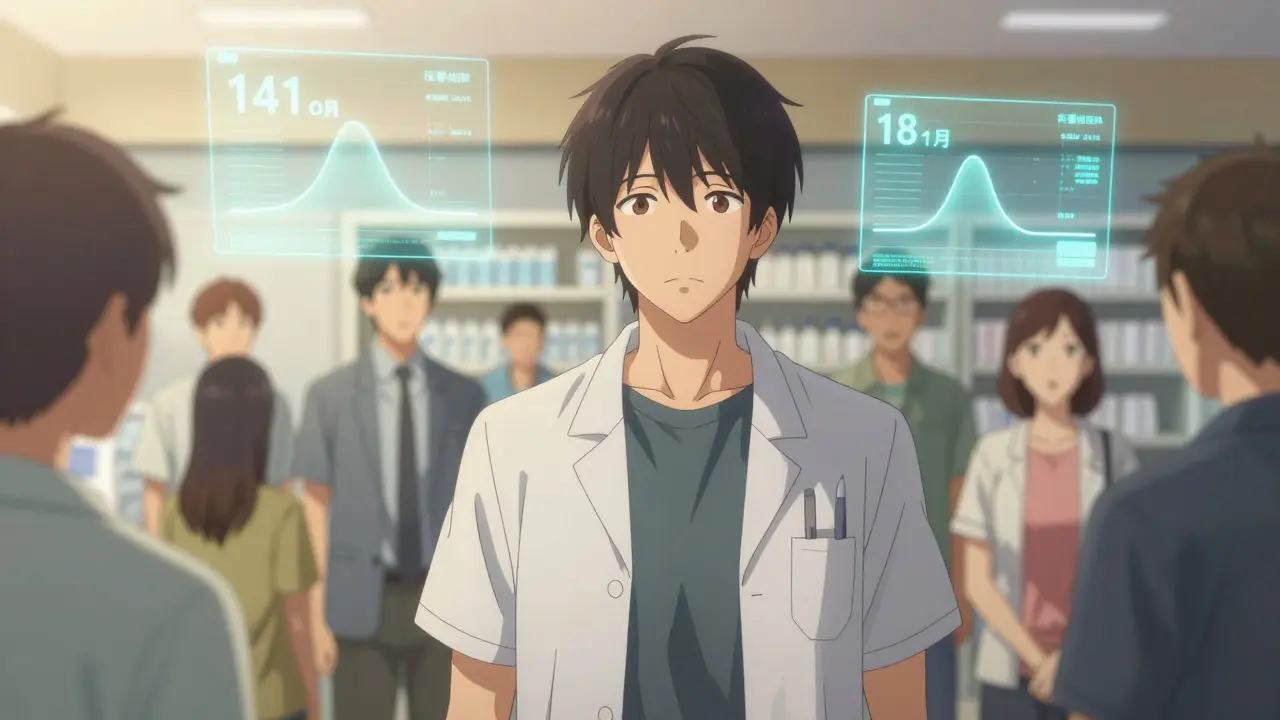

Then there are the reactions that make you question everything. Natalizumab, used for multiple sclerosis, can cause peripheral neuropathy - nerve damage - with a median onset of 141.5 days. That’s over four and a half months. A patient might think, “I’ve been on this for months, it’s working fine,” and never suspect the drug. Same with interferon beta-1a. One study found it took nearly 18 months for side effects to show up in some people. These aren’t rare. They’re predictable - if you know what to look for.

Patients on long-term medications often don’t report symptoms unless they’re severe. And if they happen after you’ve been on the drug for a year? Your doctor might write it off as aging, arthritis, or stress. That’s why 37% of side effects go unreported after treatment stops - because no one thinks to look back.

How Doctors Use Timing to Diagnose

It’s not just about when symptoms start - it’s about the pattern. Researchers use something called the Weibull distribution to map risk over time. If the shape parameter (β) is below 1, risk drops after the first few days - that’s early-onset. If it’s above 1, risk climbs over time. Most side effects (78%) fall into the early category. But that doesn’t mean the others don’t matter.

Hospitals are starting to build this into their systems. Mayo Clinic added timing algorithms to their electronic records. Since January 2022, they’ve caught 22% more adverse reactions just by flagging symptoms that line up with known drug patterns. If you get a rash 10 days after starting a new antibiotic, the system pops up: “Ciprofloxacin - median onset: 2 days. Could be related.”

Regulators now require this data. Since 2020, the European Medicines Agency demands Weibull analysis for every new drug application. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative has analyzed over 47 million patient records to build baseline timing profiles for common drugs. This isn’t science fiction - it’s standard practice now.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to use this knowledge. Keep a simple log: start date of the drug, when symptoms began, what they felt like, and how bad they were. If you’re on a new medication, ask your pharmacist: “What’s the usual time for side effects to show up?”

Don’t assume a symptom is unrelated just because it showed up after a month. If you’ve been on a drug for six months and suddenly feel different - check the timing. Look up the drug and “side effect onset” online. You’ll find studies that match what you’re experiencing.

And if your doctor dismisses your concern because “it’s been too long”? Show them the data. A 2022 patient review on Drugs.com said it best: “I developed severe angioedema four months after starting lisinopril. My doctor didn’t connect it until I showed him the research.”

What’s Next: Personalized Timing

The future isn’t just about average times - it’s about your time. The NIH’s All of Us program is starting to build genetic models that predict when side effects will hit based on your DNA. Some people metabolize drugs faster. Others are more sensitive. In 2025, your pharmacy might give you a personalized timeline: “Side effects for this drug typically start between days 3-14 for people like you.”

Wearable tech is also stepping in. Johnson & Johnson is testing how glucose monitors can track how diabetes drugs affect people in real time - not just blood sugar, but also nausea, fatigue, or dizziness. If your wearable picks up a pattern matching known drug reactions, it could alert you before you even notice.

Bottom Line

Side effects aren’t random. They follow patterns - fast, slow, delayed, or sneaky. Knowing when to expect them helps you catch problems early, avoid misdiagnosis, and talk smarter with your doctor. If you’re on a new medication, don’t just wait for the worst. Track the timing. Ask the right questions. And if something feels off - even months later - it might not be in your head. It might be in the drug.

How soon after starting a medication do side effects usually appear?

It depends on the drug. Some side effects, like angioedema from ACE inhibitors or nerve pain from ciprofloxacin, can start within hours or days. Others, like liver damage or nerve issues from immune drugs, may take weeks or months. Most common side effects show up within the first two weeks, but delayed reactions are well-documented and often missed.

Can a side effect appear months after starting a drug?

Yes. Drugs like interferon beta-1a and natalizumab can cause nerve damage or other reactions after 140+ days. ACE inhibitors can trigger angioedema up to six months later. These aren’t rare - they’re predictable if you know the timing patterns. Many patients and doctors miss them because they assume side effects only happen early.

Why do statins seem to cause muscle pain if studies say it’s often not the drug?

Research shows that in patients who quit statins due to muscle pain, about half felt better within three days - whether they were taking the real drug or a placebo. This suggests the pain is often psychological (called the nocebo effect), triggered by fear of side effects. But that doesn’t mean no one gets real muscle damage - it just means the line between real and perceived is blurry, and timing alone isn’t proof.

How do doctors tell if a symptom is from a drug or something else?

They look at timing, symptoms, and history. If a rash appears 10 days after starting a new antibiotic, it’s likely related. If fatigue shows up after six weeks on a new seizure drug, that’s a red flag. Tools like the Weibull model help predict these patterns. Hospitals now use electronic alerts that flag symptoms matching known drug timelines. Still, it’s not perfect - especially for conditions with natural fluctuations, like MS or depression.

Are some people more likely to get delayed side effects?

Yes. Women tend to get certain side effects faster - like ciprofloxacin-induced nerve pain. Genetics also play a role. People with certain liver enzyme variants metabolize drugs slower, which can delay or worsen reactions. The NIH’s All of Us program is building models to predict this using DNA, so in the future, your risk timeline could be personalized.

What should I do if I think a side effect is from my medication?

Don’t stop the drug without talking to your doctor. But do track when the symptom started, how it changed, and whether it got worse or better over time. Bring that info to your appointment. Look up the drug and “time to onset side effects” online - you’ll find studies that match your experience. If your doctor dismisses it, ask: “Is this within the known timing window for this drug?” Knowledge is your best tool.

Ellie Norris

February 1, 2026 AT 20:56i started lisinopril last year and got this weird lip swelling at month 5… my doctor thought it was allergies. i almost died before i found this article. thanks for spelling it out like this 🙏

Marc Durocher

February 1, 2026 AT 20:59statins giving you muscle pain? congrats, you’re human. also congrats you’re not the first person to blame the pill for your body saying ‘hey maybe i need to sleep more’ 😅

larry keenan

February 3, 2026 AT 12:36The temporal dynamics of pharmacologically induced adverse events are often confounded by the nocebo effect and confounding comorbidities. The Weibull distribution provides a robust framework for modeling hazard functions over time, particularly in longitudinal cohort data. Regulatory agencies now mandate this analytical approach to improve signal detection in post-marketing surveillance.

Nick Flake

February 5, 2026 AT 03:45bro. this is the most important thing i’ve read this year. 🥹 imagine if we all just… checked the clock? like, what if your fatigue isn’t ‘aging’ but your body screaming ‘this pill is not your friend’? we’re so quick to blame ourselves. maybe it’s not you. maybe it’s the damn pill waiting to strike at month 7. 🫂

Akhona Myeki

February 5, 2026 AT 16:45Why does the West always assume it invented medical awareness? In India, we’ve known for centuries that Ayurvedic herbs have delayed effects too. This isn’t news. Just rebranded with fancy graphs and American funding.

Chinmoy Kumar

February 5, 2026 AT 20:23so true! i took gabapentin for 3 weeks felt fine then bam-total brain fog at day 24. thought it was burnout. turned out it was the med. now i keep a little log on my phone. small thing, big difference 😊

Brett MacDonald

February 6, 2026 AT 03:02so like… if i feel weird after 4 months… is it the drug or did i just finally notice my life is a dumpster fire

Sandeep Kumar

February 6, 2026 AT 23:47Why do we need studies to tell us drugs can mess you up after months? Any idiot with a pulse knows this. The real problem is doctors who think patients are dumb. We’re not stupid. We just want answers not condescension

Gary Mitts

February 8, 2026 AT 15:41Track it. Don’t guess. Simple.

clarissa sulio

February 10, 2026 AT 00:41So what you’re saying is, if I feel bad after six months, it’s probably not me being lazy or dramatic? Radical.

Hannah Gliane

February 11, 2026 AT 08:44Wow. So people are finally waking up to the fact that Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know side effects can take months? 🤡 I’ve been saying this since 2019. And yes, your ‘stress’ is probably your liver screaming. Also, you’re probably on too many meds. Just saying.

Murarikar Satishwar

February 12, 2026 AT 00:40Excellent breakdown. I’ve been a pharmacist for 12 years and I still see patients dismiss symptoms because ‘it’s been too long.’ This data should be printed on every prescription bottle. Knowledge is power-and safety.

Dan Pearson

February 12, 2026 AT 02:58Ohhh so now it’s the drug’s fault? 😂 I’ve been on metformin for 8 years and I’m still alive. Meanwhile my cousin took one pill and started crying about ‘toxicity.’ Maybe stop Googling and start living? Also, I’m from Texas. We don’t need algorithms to tell us when to stop taking pills. We just stop.

Bob Hynes

February 12, 2026 AT 21:55As a Canadian, I gotta say-this is why our healthcare system works better. We don’t wait for symptoms to hit 6 months before we listen. We track. We ask. We change. No need for fancy stats. Just good ol’ patient-centered care. 🇨🇦❤️