Generic drugs are everywhere. Nine out of ten prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics. Yet, they make up just 17% of total drug spending. That’s not a mistake. It’s the result of cost-effectiveness analysis-a quiet but powerful tool shaping what drugs get covered, what patients pay, and how much the system saves.

Why generics aren’t just cheaper-they’re smarter

People assume generics are cheap because they’re copycats. That’s not the full story. A generic version of a drug isn’t just a copy of the brand-name pill. It’s a version that’s been proven to work the same way, down to the active ingredient, dose, and how your body absorbs it. The FDA requires this. But here’s what most people miss: the real savings come from competition, not just copying. When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic enters. Prices drop by about 39%. With two generics on the market? Prices fall 54%. By the time six or more companies are selling the same drug, prices are more than 95% below the original brand price. That’s not inflation-it’s market dynamics at work. And cost-effectiveness analysis is how payers, hospitals, and insurers measure that drop in real terms.How cost-effectiveness analysis actually works

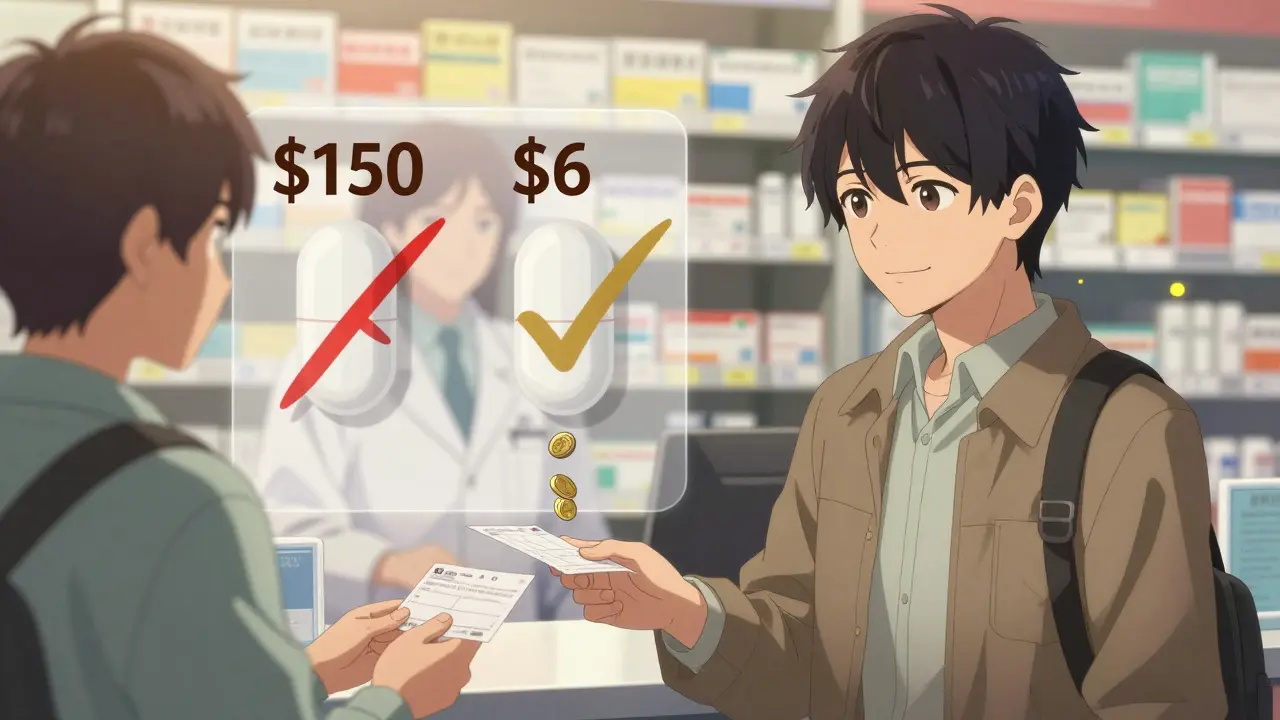

Cost-effectiveness analysis doesn’t just compare prices. It compares cost to health outcomes. The most common metric is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, or ICER. That’s the extra cost you pay for one extra quality-adjusted life year (QALY). A QALY isn’t just about living longer-it’s about living better. If a drug helps someone avoid a stroke, stay out of the hospital, or walk without pain, that’s a QALY. For generics, the math is simple: if two drugs do the same thing, but one costs $10 and the other costs $150, the cheaper one wins-unless there’s a real clinical reason to pick the pricier one. But here’s the twist: sometimes, the cheaper option isn’t obvious. A 2022 study in JAMA Network Open looked at the top 1,000 most-prescribed generic drugs. They found 45 of them were priced way higher than other drugs in the same therapeutic class. One drug, used for high blood pressure, cost 15.6 times more than another generic that worked just as well. Switching to the cheaper version would have saved $6.6 million in a single year. That’s not a small savings. That’s a system-wide opportunity.The hidden trap: high-cost generics

You’d think generics are all low-cost. But that’s not true. Some generic drugs are shockingly expensive. Why? Because they’re not competing. Sometimes, only one company makes a certain generic. Sometimes, the drug has a weird dosage form-like a slow-release capsule or a liquid that’s hard to make. That limits competition. And when competition drops, prices creep back up. Even worse, some generics are priced higher than other drugs in the same class that treat the same condition. This is called therapeutic substitution. For example, if Drug A and Drug B both treat depression and work the same, but Drug A is a generic that costs $120 and Drug B is a different generic that costs $6, the system should switch. But often, it doesn’t. Why? Because Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) profit from the spread between what they pay pharmacies and what they charge insurers. If the $120 drug gives them a bigger spread, they keep it on the formulary-even if it’s not the best value. This isn’t theory. It’s happening in real time. The JAMA study showed that generics substituted by different drugs in the same class had prices 20.6 times higher than their alternatives. That’s not pricing-it’s a flaw in the system.

What cost-effectiveness analysis misses

Here’s the biggest problem: most cost-effectiveness studies don’t look ahead. A 2021 ISPOR conference paper found that 94% of published analyses didn’t account for future generic entry. They looked at today’s prices and assumed they’d stay the same. But if a drug’s patent expires in 18 months, its price will drop. If you don’t model that, you make the wrong call. Imagine you’re deciding whether to cover a new brand-name drug. You run a cost-effectiveness analysis. You compare it to the current generic price. The brand looks expensive. You reject it. But what if that generic is going to be replaced by three cheaper versions next year? Now you’ve blocked access to a drug that might be better for some patients, just because you didn’t look ahead. Experts like Dr. John Garrison warn this creates a distortion. If analysts ignore patent cliffs, manufacturers have no incentive to innovate. Why develop a new drug if the cost-effectiveness models will always assume the old one will be cheap? That’s not just bad math-it’s bad policy.How the U.S. compares to the rest of the world

In Europe, almost every major health agency uses formal cost-effectiveness analysis to decide what drugs to cover. They look at ICERs. They adjust for future generics. They update their decisions as new data comes in. In the U.S.? Only 35% of commercial insurers use formal CEA. Most rely on formulary lists created by PBMs, pharmacy chains, or internal committees that don’t have health economists on staff. Medicare Part D doesn’t negotiate drug prices directly. Medicaid uses Federal Supply Schedule pricing, which is better, but still outdated. The VA system is one of the few that actually tracks generic pricing in real time-and they’ve saved billions because of it. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act tried to fix this by giving Medicare more power to negotiate prices. But the real opportunity isn’t in negotiation. It’s in substitution. If payers used CEA properly, they could save billions just by switching patients from high-cost generics to low-cost alternatives.

What needs to change

There are three fixes that would make a huge difference:- Require future pricing forecasts in all CEA studies. Analysts must model when generics will enter the market and how prices will drop. The NIH has a framework for this. It’s time to make it standard.

- Eliminate spread pricing. PBMs should be paid a flat fee, not a percentage of the drug price. That removes the incentive to keep expensive generics on formularies.

- Make therapeutic substitution automatic. If Drug X and Drug Y are therapeutically equivalent, and Drug Y costs 80% less, the system should switch patients to Drug Y unless there’s a documented medical reason not to.

What patients should know

You don’t need to be an economist to save money. If you’re on a generic drug that costs more than $50 a month, ask your pharmacist: "Is there another generic for this condition that costs less?" Sometimes, the answer is yes-and switching doesn’t mean changing your treatment. It just means paying less. Don’t assume your insurance plan always picks the cheapest option. PBMs don’t work for you. They work for their bottom line. You have to be the one asking the question.What’s next for generics and cost-effectiveness

Over 300 small-molecule drugs are losing patent protection between 2020 and 2025. That’s a wave of savings waiting to happen. But only if the system is ready. The future of cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t about more complex models. It’s about simpler rules: if two drugs do the same thing, pick the cheaper one. If a cheaper alternative exists, switch. If a patent is about to expire, plan ahead. The math is clear. The savings are real. The only question left is: who’s going to act on it?What is cost-effectiveness analysis for generic drugs?

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) compares the cost of a generic drug to the health outcomes it produces-like extra years of healthy life-relative to other treatment options. It helps determine whether a generic drug provides the best value for money, especially when compared to brand-name drugs or other generics.

Why are some generic drugs so expensive?

Some generics are expensive because there’s little competition-sometimes only one manufacturer makes the drug. Others are priced high because of complex dosage forms, like extended-release pills or special formulations. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) may also keep high-cost generics on formularies because they profit from the price difference between what they pay pharmacies and what insurers pay.

How much can switching to a cheaper generic save?

A 2022 JAMA study found that replacing just 45 high-cost generics with lower-cost therapeutic alternatives saved $6.6 million in a single year. In some cases, switching cut costs by 90%-from $7.5 million down to under $900,000. Even small switches, like choosing one generic over another in the same class, can save hundreds per patient annually.

Do insurance plans always pick the cheapest generic?

No. Many plans don’t use formal cost-effectiveness analysis. Instead, they rely on Pharmacy Benefit Managers who may prioritize drugs with higher rebates or spreads, not lower prices. Just because a drug is on your formulary doesn’t mean it’s the most affordable option.

Can cost-effectiveness analysis predict future generic prices?

Yes, but most studies don’t. A 2021 study found that 94% of published cost-effectiveness analyses ignored future generic entry. Experts say analyses should model price drops after patent expiration to avoid biased decisions. Tools from the NIH and VA now include these projections, but they’re not yet standard practice.

How do generics save money for the healthcare system?

Generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion between 2007 and 2017. They account for 90% of prescriptions but only 17% of drug spending. That’s because competition drives prices down-sometimes by more than 95% after multiple generics enter the market.

Jody Patrick

December 17, 2025 AT 14:53Generic drugs? More like generic scams. The system’s rigged. PBMs laugh all the way to the bank while patients get stuck with $120 pills for a $6 drug. Wake up, America.

Radhika M

December 18, 2025 AT 06:04Simple truth: if two medicines do the same thing, pick the cheaper one. No magic, no fancy math. Just common sense. Many people in India know this already - we’ve been doing it for years.

Philippa Skiadopoulou

December 20, 2025 AT 06:04The data presented is compelling. The systemic failure to integrate future pricing dynamics into cost-effectiveness models represents a significant oversight in health economics. The absence of predictive modeling undermines rational formulary decisions.

Pawan Chaudhary

December 21, 2025 AT 17:59This is actually really hopeful! We already have the tools to fix this. If we just switch to the cheaper generics, we can save so much money - and help so many people. Let’s do it!

Anna Giakoumakatou

December 23, 2025 AT 17:51Oh, so now we’re pretending cost-effectiveness is about ‘saving money’? How quaint. The real cost is measured in dignity, not dollars. But sure, let’s reduce human health to a spreadsheet. The VA does it, so it must be noble.

Sam Clark

December 24, 2025 AT 09:14Thank you for this thorough and well-researched analysis. The three proposed reforms - forecasting generic entry, eliminating spread pricing, and mandating therapeutic substitution - are not only logical but ethically imperative. Implementation requires coordinated policy action, but the evidence is unequivocal.

Chris Van Horn

December 25, 2025 AT 22:44YOU PEOPLE ARE IDIOTS. The FDA doesn’t even test generics properly. My cousin’s blood pressure spiked after switching. You think math fixes biology? LOL. You’re all just profit-driven robots. And PBMs? They’re the real villains. Stop pretending this is about ‘value.’ It’s about control.

Peter Ronai

December 26, 2025 AT 16:5094% of studies ignore future generics? That’s not a flaw - it’s a conspiracy. The pharma lobby pays off the analysts. The whole system is a Ponzi scheme disguised as science. And you wonder why people don’t trust medicine anymore? Because you’re all lying to them.

Steven Lavoie

December 28, 2025 AT 16:28I’ve worked in public health across five countries. What’s striking is how the U.S. treats cost-effectiveness like an optional spreadsheet exercise, while places like the UK and Canada treat it as foundational policy. It’s not about being cheap - it’s about being smart. And we’re not.

Anu radha

December 30, 2025 AT 04:19My mom takes a generic for cholesterol. She pays $4. I asked her pharmacist - there’s another one for $1. She didn’t know. People need to know this stuff. It’s not hard.

Salome Perez

January 1, 2026 AT 02:40The brilliance of this piece lies in its elegant simplicity: if two drugs are therapeutically equivalent, the cheaper one should be the default. No exceptions. No spreads. No lobbying. Just clinical equivalence + economic justice. The VA does it. Why can’t the rest of us? The tools are here. The will is not. And that’s the real tragedy - not the price tag.