When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize you’re choosing between two very different kinds of medicine. One is made by just one company - no other versions exist. The other? Dozens of manufacturers make it, and most of them cost a fraction of the original. This isn’t just a pharmacy detail. It’s about your wallet, your health, and whether your medicine actually works the same way every time.

What’s the difference between single-source and multi-source drugs?

A single-source drug is the original brand-name medicine, and no generic version has been approved yet. Think of it like the first iPhone - only Apple made it. These drugs are often new, expensive, and protected by patents or exclusivity rights. Examples include Humira before 2023, or newer cancer drugs like Keytruda. There’s only one maker, and they control the price.

A multi-source drug means the brand-name version is still around, but now there are also generic versions made by other companies. These generics have the same active ingredient, dose, and way of taking it as the brand. They’ve been tested and approved by the FDA to work the same way. Think of it like buying a phone charger - you can get the Apple one, or a cheaper one that works just as well. Most drugs you take fall into this category. About 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are multi-source drugs.

Why does this matter for your out-of-pocket costs?

Let’s say you’re on a medication that costs $587 a month - that’s the average for single-source drugs, according to a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey. Switch to the generic version? That same drug might now cost $132 a month. That’s not a typo. That’s $455 saved every month.

But here’s the catch: even when a drug becomes multi-source, your insurance might not automatically switch you. Many plans use something called a formulary - a list of approved drugs. Single-source drugs are often on higher tiers, meaning you pay more. Insurers may require you to try the cheaper generic first (called step therapy). If you refuse, you could pay full price.

And here’s something most patients don’t know: the price you see on the shelf isn’t what the pharmacy actually gets paid. PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) set a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) for generics - often 50-60% below the brand’s list price. Your insurance pays that MAC, not the full price. So even if the brand drops its price, your generic still costs way less.

Are generic drugs really the same?

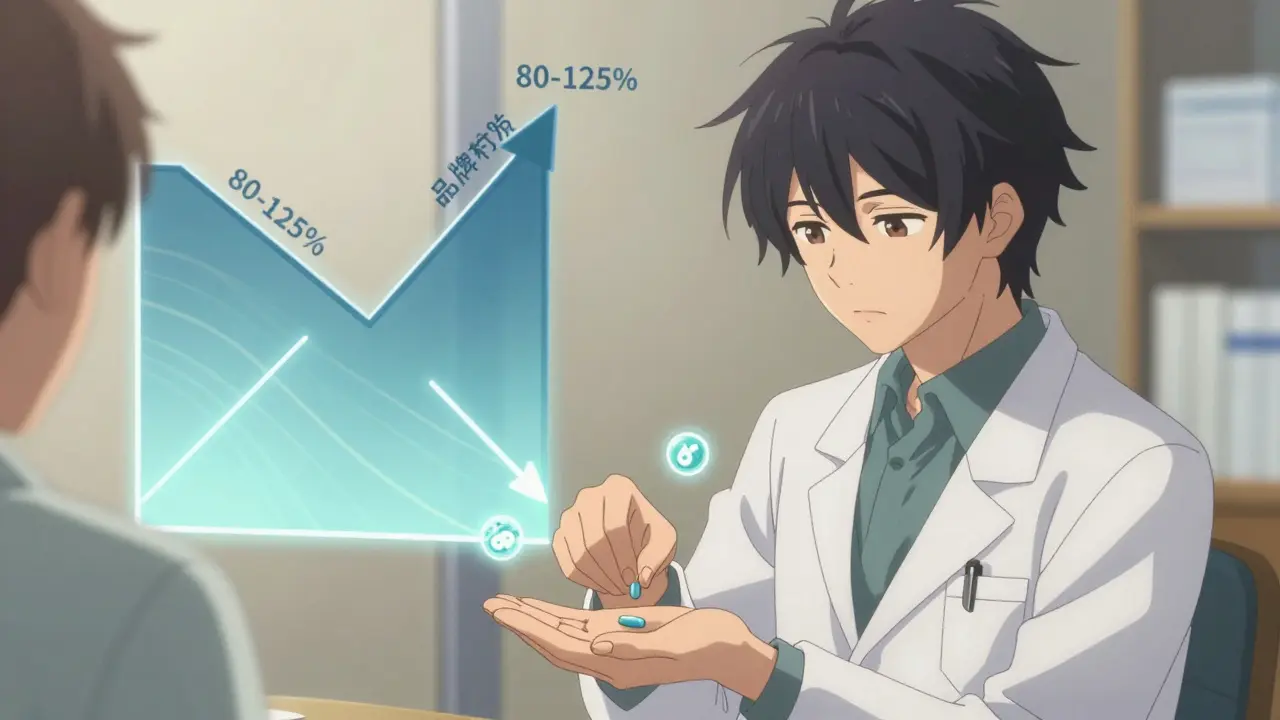

The FDA says yes. All generics must prove they’re bioequivalent - meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream within a very tight range (80-125% of the brand). This isn’t a guess. It’s lab-tested, reviewed, and approved.

So why do some patients say, ‘This generic doesn’t work like the last one’?

It’s not that the medicine is different - it’s that the inactive ingredients (fillers, dyes, coatings) can vary. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like blood thinners (warfarin), seizure meds (phenytoin), or thyroid hormones (levothyroxine) - tiny changes can affect how your body responds. That’s why pharmacists are trained to alert you if your generic manufacturer changes. If you notice new side effects or your condition feels off after a switch, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. It’s not always the drug. It could be the formulation.

On Drugs.com, multi-source drugs have an average rating of 4.2 out of 5. The brand-name versions? 4.5. That small gap comes from a small but vocal group of patients who swear their original brand worked better. The FDA’s position? There’s no clinical proof. But they also acknowledge that some people are sensitive to changes - even if the science says it shouldn’t matter.

Why do prices go up on generics?

It sounds backwards. How can a generic drug - made by 10 companies - cost more than it did last year?

In 2023, prices for multi-source drugs jumped 26% - much higher than single-source drugs, which rose just 7.4%. But here’s the twist: the dollar increase for single-source drugs was $958. For multi-source? Only $69. So while the percentage spike looks scary, the actual cost bump is tiny.

This happens because PBMs and insurers push for the lowest price. When one generic manufacturer lowers their price, others follow. That’s competition. But sometimes, if one maker stops producing a drug, or if raw materials get expensive, the remaining manufacturers raise prices. That’s what caused the recent spike in some common generics like metformin and lisinopril.

Single-source drugs, on the other hand, have no competition. So their manufacturers can raise prices - and they do. But here’s the hidden system: those price hikes are often matched by bigger rebates to PBMs. That means the list price goes up, but the net price (what the insurer pays) doesn’t change much. Patients, however, still pay based on the list price - unless their plan uses a fixed copay. That’s why your bill might go up even if the drug’s real cost didn’t.

What should you do when your prescription changes?

Here’s a simple checklist you can use every time you refill a prescription:

- Check the name. Is it still the brand? Or did it switch to a generic? If you’re unsure, ask the pharmacist.

- Ask about the manufacturer. If you’ve had issues before, find out which company made your pill. Some patients respond better to one brand of generic than another. Write it down.

- Know your copay. Is your plan charging you more for the brand? You might be able to save money by switching - even if you don’t think you need to.

- Call your insurance. Ask: ‘Is this drug on my formulary? What tier is it? Is there a cheaper generic?’

- Don’t assume it’s the same. If you feel different after a switch - even if it’s just a little - tell your doctor. Don’t wait for it to get worse.

Many patients report needing 2-3 pharmacy visits before they feel comfortable navigating these systems. That’s normal. You’re not being difficult. You’re being smart.

What’s changing in 2025?

The FDA is speeding up generic approvals. Thanks to GDUFA III, the goal is to approve new generics in just 10 months - down from over a year. That means more drugs will become multi-source faster. Humira, which was single-source for 14 years, became multi-source in 2023. More drugs like it are coming.

But here’s a twist: some brand companies release their own generics - called ‘authorized generics.’ These are made by the original company, just sold under a different label. They’re not cheaper than other generics, but they’re still cheaper than the brand. This lets the company keep some market share while appearing to support lower prices.

Also, new laws like the Inflation Reduction Act hit single-source drugs harder. If their price goes up faster than inflation, manufacturers must pay a rebate to Medicare. That’s putting pressure on companies to keep prices stable - or risk losing money.

Bottom line: You have more power than you think

You don’t have to accept whatever your prescription says. You can ask questions. You can compare prices. You can ask for the generic. You can ask why you’re being charged more for the brand. You can ask if your pharmacist switched your manufacturer - and if you’re okay with it.

Most people don’t know this: 86% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with multi-source drugs. That’s because they’re safe, effective, and affordable. The system isn’t perfect. Switches happen. Prices fluctuate. But the goal is clear: get you the medicine you need without breaking the bank.

If you’re paying hundreds a month for a drug that has a generic version, you’re likely overpaying. Talk to your pharmacist. Call your insurance. Ask for the lowest-cost option. It’s your right - and your money.

Aliza Efraimov

December 30, 2025 AT 03:37I switched my levothyroxine last year and thought I was having a panic attack-sweating, heart racing, zero sleep. Turns out, the generic had a different filler. My pharmacist flagged it when I asked. Don’t ignore those little changes. Your body notices before your brain does. 🤕

David Chase

December 30, 2025 AT 12:09LOL so now we’re supposed to trust generics because the FDA says so?? 😂 Like the same agency that let Purdue Pharma sell OxyContin like candy?? 🤡 I’ve seen people crash after switching-your ‘bioequivalent’ BS doesn’t fix the fact that Big Pharma controls the supply chain. Pay attention, people. This is rigged.

Joe Kwon

January 1, 2026 AT 12:07As a pharmacist, I see this daily. The MAC pricing system is a mess-it incentivizes switching to the cheapest generic, even if it’s from a manufacturer with a history of quality issues. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are solid, but they don’t account for patient variability. I always tell patients: if you feel off after a switch, document it. Bring lab results. Push back. You’re not being difficult-you’re being your own advocate.

Fabian Riewe

January 2, 2026 AT 16:54My dad’s on warfarin. We used to get the brand, then switched to generic-no issues for 2 years. Then one refill, he started bruising like a cartoon. Turned out the new maker used a different coating that changed absorption. We went back to the old generic (yes, same drug, different company) and he’s fine. Bottom line: know your manufacturer. Write it down. It matters more than you think.

Jasmine Yule

January 3, 2026 AT 03:34Why do people act like this is new info? 🤦♀️ I’ve been asking for generics since 2018. My insurance even covered them before the law forced them to. If you’re paying full price for a drug that has a $10 generic version, you’re not being loyal-you’re being exploited. Ask your pharmacist to show you the MAC list. It’s eye-opening.

Sharleen Luciano

January 3, 2026 AT 11:19How quaint. You all treat generics like they’re some kind of moral victory. But let’s be honest-most people don’t have the time, energy, or education to navigate PBM formularies, MAC lists, or bioequivalence thresholds. This isn’t empowerment. It’s a system designed to offload complexity onto the most vulnerable. And you’re patting yourselves on the back for playing the game?

Henriette Barrows

January 4, 2026 AT 16:40My sister’s on seizure meds. She switched generics twice and had two seizures in 3 weeks. No joke. The pharmacy didn’t even tell her it changed. She’s fine now, but only because her neurologist insisted on tracking the manufacturer. Please-don’t assume it’s the same. Ask. Always ask.

Russell Thomas

January 5, 2026 AT 22:41Wow. So the FDA says it’s the same, but somehow the brand works better? Sounds like placebo effect to me. Or maybe you’re just addicted to the brand’s fancy packaging and blue pill shape. Grow up. It’s medicine, not a luxury perfume.

Tamar Dunlop

January 7, 2026 AT 04:48In Canada, we don’t have the same PBM-driven chaos. Generics are uniformly priced and monitored by Health Canada. If a patient reports adverse effects after a switch, the manufacturer is required to investigate. It’s not perfect, but it’s less of a lottery. I wish the U.S. would adopt similar safeguards-especially for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs.

Jim Rice

January 7, 2026 AT 08:07Wait-you’re telling me I should switch to a generic because it’s cheaper? But what if the brand is the only one that doesn’t make me nauseous? You’re ignoring real patient experience for some spreadsheet logic. Your ‘science’ doesn’t account for the fact that I’m not a lab rat.

Greg Quinn

January 7, 2026 AT 11:51It’s fascinating how we treat medicine like a commodity when it’s deeply personal. The body doesn’t care about patents or rebates-it cares about consistency. Maybe the real issue isn’t generics vs. brands-it’s that we’ve normalized instability in something that should be predictable. We treat health like a subscription service. It’s not.

Lisa Dore

January 8, 2026 AT 09:39Just had my first refill of metformin after the price hike. $2.50 at Walmart. I cried. Not because it’s cheap-but because I know someone out there is still paying $80 for the same thing. You’re not broken if you need help asking. You’re not weak if you call your insurer. You’re just awake. Keep going.

Samar Khan

January 10, 2026 AT 08:00OMG I just switched to generic lisinopril and my BP spiked to 190/110 😱 I thought I was dying!! Turns out the new maker used a different binder. My pharmacist said it’s ‘within FDA limits’ but I’m not buying it. I’m going back to the brand. My life > your savings. 💔