Sudden shortness of breath could be more than just being out of shape

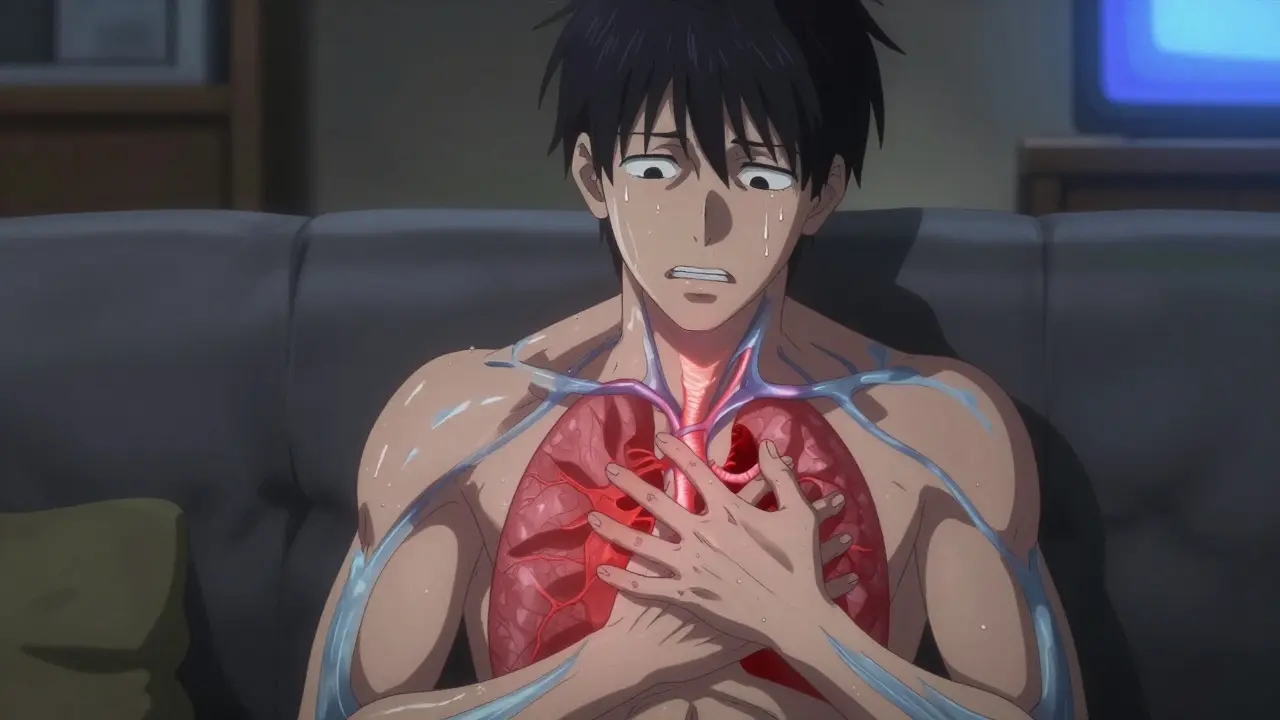

If you’ve ever felt like you can’t catch your breath-especially when you’re sitting still, climbing stairs, or just watching TV-it’s easy to brush it off. Maybe you’re tired. Maybe you’re stressed. Maybe you’re just out of shape. But when that breathlessness comes on suddenly and doesn’t go away, it could be something far more serious: a pulmonary embolism, or PE.

Pulmonary embolism happens when a blood clot, usually from a deep vein in the leg, breaks loose and travels to the lungs, blocking one or more arteries. It’s not rare. In the U.S., about 60 to 70 people out of every 100,000 get it each year. And it kills around 100,000 people annually. The scary part? Many of those deaths happen because the symptoms are ignored or mistaken for something else.

What sudden shortness of breath really looks like in PE

Eighty-five percent of people with pulmonary embolism report sudden shortness of breath as their first and most common symptom. But it doesn’t always look the same. In severe cases-when the clot is large and blocks a major artery-the breathlessness hits fast and hard. You might feel like you’re suffocating, even while lying down. In smaller clots, it might just feel like you can’t climb a flight of stairs like you used to.

It’s not just about breathing. Chest pain is the next most common sign, reported by 74% of patients. This isn’t the dull, heavy pain of a heart attack. It’s sharp, stabbing, and gets worse when you breathe in deeply or cough. People often describe it as if someone is pressing a knife into their side. That’s why so many end up in the ER thinking they’re having a heart attack.

Other signs include:

- Cough, sometimes with blood (23% of cases)

- One swollen, painful leg (44% of cases)

- Fast heartbeat (over 100 bpm in 30% of cases)

- Rapid breathing (over 20 breaths per minute in 52% of cases)

- Fainting or dizziness (14% of cases)

Here’s what makes PE so dangerous: you can have all of these symptoms and still look fine. No fever. No rash. No obvious injury. That’s why doctors miss it. A 2022 survey of 1,200 PE patients found that 68% visited a doctor at least twice before getting the right diagnosis. Many were told they had asthma, anxiety, or pneumonia.

Why diagnosis is often delayed-and what changes that

There’s no single test that screams "PE" right away. That’s why diagnosis is a puzzle. The first step is always clinical suspicion. If you’re at risk-recent surgery, long flight, cancer, pregnancy, or a history of blood clots-and you suddenly can’t breathe, PE has to be on the table.

Doctors use tools like the Wells Score or Geneva Score to estimate how likely PE is. These aren’t perfect, but they’re good at ruling it out. If the score says low risk, a blood test called D-dimer is next. D-dimer measures a substance released when clots break down. If it’s negative and your risk is low, PE is almost certainly ruled out. The test is 97% sensitive, meaning it rarely misses a real clot.

But here’s the catch: D-dimer goes up with age, infection, pregnancy, and cancer. In people over 50, it’s only about 54% specific. That means too many false positives. That’s why new guidelines now use age-adjusted D-dimer: for someone 65, the cutoff is 650 ng/mL, not 500. This reduces unnecessary scans by nearly 37% without missing more clots.

The gold standard: CTPA scan

If your risk is moderate or high, or if your D-dimer is positive, you’ll need imaging. The go-to test is a CT pulmonary angiogram, or CTPA. It’s a specialized CT scan that uses contrast dye to show the blood vessels in your lungs. It finds clots in 95% of cases and is wrong less than 5% of the time.

The scan takes less than 10 minutes. You get injected with contrast, lie on a table, and hold your breath while the machine spins around you. Radiation exposure is low-about the same as a year of natural background radiation. But it’s not for everyone. If you have kidney problems or an allergy to iodine, your doctor might choose a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan instead. It’s less common, only available at about 78% of major hospitals, but it’s safe for people who can’t have contrast.

For patients who are crashing-low blood pressure, fainting, turning blue-time is everything. In those cases, doctors skip the scan and go straight to an ultrasound of the heart. If the right side of the heart is swollen and struggling, it’s a strong sign of a massive clot. Immediate treatment starts right there.

Checking the legs: ultrasound for deep vein thrombosis

Most clots that cause PE start in the legs. So if you have swelling, pain, or warmth in one leg, an ultrasound of the deep veins is often done. It’s quick, painless, and over 90% accurate at finding clots in the large veins of the thigh and pelvis. If the leg ultrasound finds a clot, and you have symptoms like shortness of breath, you don’t always need a CTPA. The diagnosis is clear.

But here’s something many don’t realize: you can have a PE without a visible clot in your legs. About 30% of patients have no signs of DVT. That’s why you can’t rely on leg swelling alone.

Who’s at highest risk-and why it matters

Some people are at much higher risk. Cancer patients are nearly five times more likely to get PE. That’s because tumors release substances that make blood clot more easily. If you have cancer and suddenly get short of breath, don’t wait. Get checked immediately.

People who’ve had a PE or DVT before are also at risk. One in three will have another clot within 10 years. If you’ve been told you had a "blood clot" in the past, any new breathing trouble should be treated as a red flag.

Other risk factors include:

- Recent surgery (especially hip or knee replacements)

- Long flights or car rides (over 4 hours)

- Being immobilized for days (hospital stay, bed rest)

- Pregnancy and the first 6 weeks after birth

- Birth control pills or hormone therapy

- Smoking

- Obesity

It’s not just about risk factors, though. It’s about timing. D-dimer tests are most accurate if done within 24 hours of symptoms starting. After that, the chance of a false negative rises by 12% every 12 hours. So if you’re having trouble breathing, don’t wait until tomorrow.

What’s new in PE diagnosis

Diagnosis is getting faster and smarter. Hospitals are forming Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams (PERT)-special groups of doctors, radiologists, and pharmacists who jump in when a PE is suspected. In hospitals with PERT, time from arrival to treatment dropped by over 3 days, and deaths fell by 4.1%.

Artificial intelligence is helping too. New software like PE-Flow can analyze CT scans and flag clots with 93.7% accuracy. It doesn’t replace doctors, but it helps them spot small clots they might miss.

Researchers are also testing new blood markers. Right now, D-dimer is the only routine test. But in the future, a panel of markers-like soluble thrombomodulin and plasmin-antiplasmin-could give a clearer picture. Early trials show these combined tests are 98.7% accurate at ruling out PE in intermediate-risk patients.

What to do if you think you might have PE

If you have sudden shortness of breath-especially with chest pain, leg swelling, or fainting-don’t wait. Don’t call your primary care doctor and schedule an appointment for next week. Go to the emergency room. Tell them exactly what you’re feeling: "I suddenly couldn’t breathe, and it’s getting worse." Mention any recent surgery, travel, or history of clots.

Most hospitals now have clear pathways for PE. In places that use them, patients get scanned in under an hour. In ones that don’t, it can take 2 hours or more. The difference? Survival.

One hospital system cut their time-to-scan from 127 minutes to 43 minutes. Mortality dropped from 8.2% to 3.1%. That’s not magic. That’s protocol.

Bottom line: Trust your body

Shortness of breath is common. Sudden, unexplained shortness of breath is not. If it comes out of nowhere, doesn’t improve with rest, and you’re not recovering like you normally would, it’s not anxiety. It’s not asthma. It’s not just being out of shape.

Pulmonary embolism doesn’t care if you’re young, fit, or healthy. It strikes without warning. But it’s treatable-if caught in time. The tools to find it are here. The protocols exist. What’s missing is awareness.

Know the signs. Speak up. Demand action. Your breath-and your life-depend on it.

Can a pulmonary embolism go away on its own?

Sometimes small clots can dissolve on their own over weeks or months, but this is unpredictable and dangerous. Larger clots can cause permanent lung damage, heart strain, or sudden death. Even small clots can grow or break off again. Treatment with blood thinners is standard because it stops clots from getting bigger and reduces the risk of new ones forming. Never wait to see if it "goes away."

Is a pulmonary embolism the same as a heart attack?

No. A heart attack happens when a clot blocks blood flow to the heart muscle. A pulmonary embolism is a clot blocking blood flow in the lungs. They both cause chest pain and shortness of breath, but the causes and treatments are different. Heart attacks are diagnosed with EKG and cardiac enzymes; PE is diagnosed with CT scans and D-dimer. Mistaking one for the other can delay life-saving treatment.

Can you have a pulmonary embolism without any symptoms?

Yes, especially if the clot is very small. Some people have tiny clots that don’t cause noticeable symptoms and are found accidentally during scans for other reasons. But even these can be dangerous if they grow or if more clots form. Doctors usually treat them anyway because the risk of recurrence is high. If you’re at risk for clots, regular check-ins matter-even if you feel fine.

How long does treatment for pulmonary embolism last?

Treatment usually starts with injections of blood thinners (like heparin), followed by oral pills (like rivaroxaban or apixaban). For a first PE with a clear trigger-like surgery or a long flight-treatment lasts 3 months. If there’s no clear trigger, or if you have cancer or a genetic clotting disorder, treatment may continue for 6 months, a year, or even lifelong. Your doctor will decide based on your risk of recurrence.

Can I fly after having a pulmonary embolism?

Yes, but not right away. Most doctors recommend waiting at least 2 to 4 weeks after diagnosis and starting blood thinners. During the flight, wear compression socks, stay hydrated, and walk around every hour. The risk of another clot is highest in the first few weeks after diagnosis. If you’re planning a long trip, talk to your doctor first. They may adjust your medication or recommend additional precautions.

Does walking help with pulmonary embolism?

Walking doesn’t dissolve the clot, but it helps prevent new ones and improves circulation. After diagnosis, doctors encourage gentle movement as soon as it’s safe. Bed rest used to be standard, but now we know it increases the risk of more clots. Light walking, stretching, and avoiding long periods of sitting are key parts of recovery. But don’t push yourself. If walking makes you short of breath or dizzy, stop and rest.

Laura Arnal

January 29, 2026 AT 11:29Jasneet Minhas

January 30, 2026 AT 08:55Eli In

January 31, 2026 AT 02:55Megan Brooks

January 31, 2026 AT 21:16Ryan Pagan

February 1, 2026 AT 21:43Paul Adler

February 2, 2026 AT 03:43Kristie Horst

February 2, 2026 AT 05:20Andy Steenberge

February 4, 2026 AT 05:19Laia Freeman

February 5, 2026 AT 18:42rajaneesh s rajan

February 6, 2026 AT 09:45