Thalidomide is one of the most infamous drugs in medical history-not because it didn’t work, but because it worked too well in the wrong way. In the late 1950s, it was sold as a safe, gentle solution for morning sickness and insomnia. Pregnant women took it without hesitation. By 1961, thousands of babies were born with missing or stunted limbs, deafness, heart defects, and internal organ damage. The cause? A drug that crossed the placenta and shattered fetal development during a narrow, invisible window of pregnancy. This is the story of how a medication became a global tragedy-and how it forced medicine to change forever.

The Rise of a "Miracle Drug"

Thalidomide was developed in West Germany in 1954 by Chemie Grünenthal GmbH. It was marketed as a non-addictive sedative and anti-nausea remedy. Unlike barbiturates, which carried risks of overdose and dependency, thalidomide seemed harmless. By 1957, it was available in 46 countries under names like Contergan, Distaval, and Gravol. Doctors prescribed it freely to pregnant women. At the time, there were no formal rules requiring testing for effects on unborn babies. The assumption was simple: if it was safe for adults, it was safe for fetuses.The numbers tell the scale: over one million pregnant women took thalidomide. In Germany, the UK, Canada, Australia, and Japan, it became a household name. But behind the calm reassurances, something was going terribly wrong. Babies were being born with phocomelia-limbs that looked like flippers, with hands or feet attached directly to the torso. Some had no ears. Others had cleft palates, missing eyes, or malformed hearts. Parents didn’t know why. Doctors didn’t know why. The link wasn’t obvious because the damage only happened if the drug was taken between the 34th and 49th day after the mother’s last period. That’s a window of just two weeks. Outside of it, the risk dropped sharply. Inside it, even a single dose could be enough.

The Breakthrough That Changed Everything

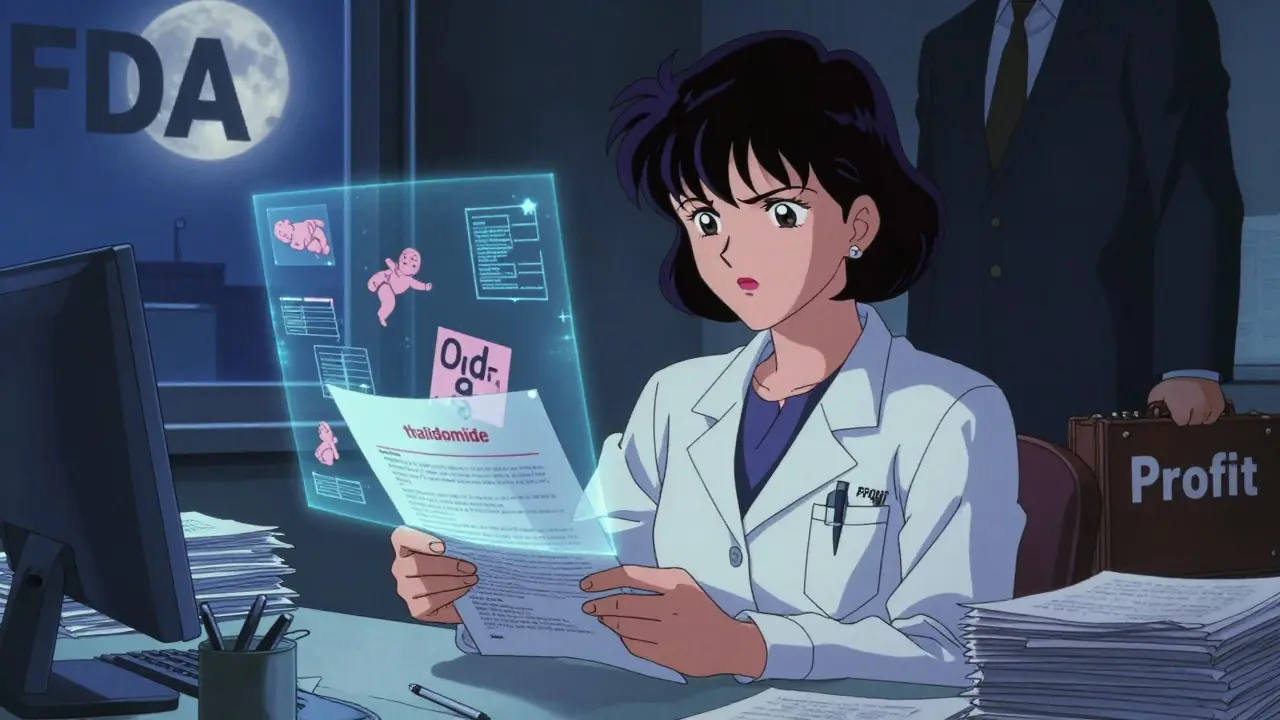

In 1961, two doctors working independently reached the same terrifying conclusion. In Australia, Dr. William McBride noticed a spike in limb defects at the Women’s Hospital in Sydney. He wrote a letter to The Lancet in June, directly linking thalidomide to the birth defects. Around the same time, in Germany, Dr. Widukind Lenz, a pediatrician, was tracking similar cases and found a pattern: nearly all affected mothers had taken thalidomide during early pregnancy. Lenz called Grünenthal on November 15, 1961, demanding they act. Two weeks later, the drug was pulled from the German market. The UK followed in early December. The U.S. government didn’t issue a warning until May 1962.Why did the U.S. escape the worst? Because a single FDA reviewer, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, refused to approve thalidomide. She questioned the safety data. She asked for more studies on fetal effects. She held firm despite pressure from the drug’s U.S. distributor, Richardson-Merrell. Her skepticism saved untold numbers of American babies. She later received the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. Her name is now on a federal medal for drug safety.

What the Drug Did to Developing Babies

Thalidomide didn’t just affect limbs. A 1964 UK government report found it could damage almost every organ system. Babies were born with:- Missing or underdeveloped arms and legs (phocomelia)

- Deafness and eye abnormalities

- Heart defects, including ventricular septal defects

- Blockages in the esophagus, anus, or duodenum

- Missing gallbladder or appendix

- Facial paralysis and cleft palate

About 40% of affected infants died within the first year. Survivors faced lifelong disabilities. Many required multiple surgeries, prosthetics, and constant medical care. Families were left with questions, grief, and anger. And for years, pharmaceutical companies denied responsibility. It wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that compensation programs began in earnest.

The Hidden Danger: Neurotoxicity and the Delayed Warning

Long before the birth defects were recognized, there were signs of something else. In late 1960, patients-mostly adults taking thalidomide for sleep or anxiety-began reporting tingling in their hands and feet. Some developed thumb weakness and numbness. Grünenthal added a small warning to the packaging in 1960: “prickling and numbness.” But no one connected this to the unborn. The neurological damage in adults was called peripheral neuropathy. In babies, it was called phocomelia. Both were caused by the same mechanism, just at different stages of development.It wasn’t until 2018-over 60 years after the first baby was born-that scientists finally understood how thalidomide worked. It binds to a protein called cereblon. This protein normally helps regulate genes that guide limb growth in embryos. When thalidomide attaches to cereblon, it shuts down those genes. The limbs don’t form. The same mechanism also explains why thalidomide works against cancer: it disrupts blood vessel growth in tumors. The drug that caused birth defects also became a weapon against multiple myeloma.

Thalidomide’s Second Life: From Tragedy to Treatment

In 1964, Dr. Jacob Sheskin, a doctor in Israel, gave thalidomide to a leprosy patient suffering from painful skin sores. The sores vanished. That accidental discovery led to its FDA approval in 1998 for erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a complication of leprosy. Then, in 2006, it was approved for multiple myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells. Clinical trials showed that thalidomide improved progression-free survival from 23% to 42% at three years. Overall survival jumped from 75% to 86%. But the side effects were brutal: up to 60% of patients had to stop taking it due to nerve damage, drowsiness, or constipation.Today, thalidomide is still used-strictly controlled. In the U.S., it’s only available through the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS). Women of childbearing age must use two forms of birth control, have monthly pregnancy tests, and sign legal agreements acknowledging the risks. Men must use condoms, because thalidomide can be present in semen. The drug is no longer sold over the counter. It’s not even prescribed lightly. Every bottle comes with a warning label that says: “This drug can cause severe birth defects. Do not take if pregnant or planning pregnancy.”

The Legacy: How the World Changed After Thalidomide

The thalidomide disaster didn’t just cost lives-it rewrote the rules of medicine. Before 1961, drug approval was a formality. Companies submitted data, regulators signed off, and drugs hit the market. Afterward, everything changed.In the U.S., the Kefauver-Harris Amendments of 1962 required drug makers to prove both safety and effectiveness before approval. They had to test for teratogenic effects-especially in pregnant animals. Clinical trials had to be randomized and controlled. In the UK, the Committee on the Safety of Medicines was created in 1963. Similar agencies formed in Canada, Australia, and across Europe.

Today, every drug intended for women of childbearing age must go through rigorous fetal safety testing. The FDA, EMA, and WHO all have guidelines for reproductive toxicology. Pregnancy categories (like Category X) were created to warn doctors and patients. And in every medical school, thalidomide is still taught as the case study that changed everything.

What We Still Don’t Know

Even now, decades later, we don’t fully understand why some women who took thalidomide had affected babies and others didn’t. Genetics, metabolism, dosage timing-all may play a role. We still don’t have a perfect way to predict who’s at risk. That’s why the rules remain strict: no exceptions, no compromises.Thalidomide is a reminder that medicine is not infallible. A drug can be safe for millions and deadly for one unborn child. The lesson isn’t just about testing-it’s about humility. It’s about listening to the quiet signals before they become screams. It’s about trusting the people who say, “Something’s wrong,” even when no one else sees it yet.

Modern Teratogenic Medications to Watch

Thalidomide isn’t the only drug that can harm a developing fetus. Today, other medications carry similar risks:- Isotretinoin (Accutane) - Used for severe acne. Causes skull, heart, and brain defects. Requires mandatory pregnancy testing and contraception.

- Valproic acid - Used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder. Linked to neural tube defects and autism spectrum disorders.

- Methotrexate - A chemotherapy drug. Causes miscarriage and multiple birth defects.

- ACE inhibitors - Used for high blood pressure. Can cause kidney damage and low amniotic fluid in the second and third trimesters.

If you’re pregnant or planning pregnancy, always ask: “Is this drug safe for my baby?” Don’t assume a prescription is safe. Don’t rely on a pharmacist’s word alone. Talk to your doctor. Check the FDA’s pregnancy categories. Use reliable sources like the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS).

Why This Matters Today

We live in an age of rapid drug development. New medications for cancer, autoimmune disease, and mental health are approved faster than ever. But the same risks remain. A drug that’s safe for a 35-year-old woman might be deadly to her 4-week-old embryo. The thalidomide tragedy teaches us that safety isn’t a checkbox-it’s a culture. It’s about asking hard questions, listening to warning signs, and never assuming “it’s been used for years, so it must be fine.”Every time a woman takes a medication during pregnancy, there’s a silent calculation: risk versus benefit. Thalidomide showed us what happens when that calculation goes wrong. It also showed us what happens when we get it right-when regulators listen, when doctors question, when patients are informed.

The scars of thalidomide remain. But so does its lesson: that protecting the unborn isn’t just a medical duty-it’s a moral one.

Can thalidomide cause birth defects even if taken once?

Yes. Even a single dose of thalidomide taken during the critical window-between 34 and 49 days after the last menstrual period-can cause severe birth defects. The drug acts rapidly on developing limb buds and other structures, and there is no known safe threshold. This is why it’s classified as one of the most potent human teratogens ever identified.

Is thalidomide still used today?

Yes, but under extreme restrictions. Thalidomide is approved in the U.S. and other countries for treating erythema nodosum leprosum and multiple myeloma. It’s only available through the STEPS program, which requires strict birth control, monthly pregnancy tests, and signed consent forms for both men and women. It is never prescribed for morning sickness or sleep issues.

Why didn’t animal testing catch the danger earlier?

Animal testing failed because different species metabolize thalidomide differently. Rats and mice, commonly used in early tests, did not show the same birth defects as humans. It wasn’t until primate studies were done in the early 1960s that the risk became clear. This gap exposed a major flaw in drug safety protocols-and led to new requirements for testing in multiple species, including primates, before human trials.

Are there safer alternatives to thalidomide for pregnant women?

Thalidomide should never be used during pregnancy. For conditions it treats-like leprosy complications or multiple myeloma-there are alternatives such as lenalidomide or pomalidomide, but these are also teratogenic and carry similar restrictions. For morning sickness, doxylamine and pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) are FDA-approved and considered safe. Always consult a doctor before taking any medication while pregnant.

How did the thalidomide tragedy change how drugs are tested for pregnancy safety?

Before thalidomide, drug safety testing focused almost entirely on adult effects. Afterward, regulatory agencies worldwide required mandatory reproductive toxicity studies. This includes testing in pregnant animals across multiple species, assessing effects on fetal development, and evaluating placental transfer. Today, all new drugs intended for women of childbearing age must undergo these tests before approval. The FDA’s pregnancy categories (A, B, C, D, X) were created to communicate risk levels to clinicians and patients.

Kat Peterson

January 23, 2026 AT 03:10OMG I CANNOT BELIEVE WE’RE STILL USING THIS DRUG 😭💔 I mean, like, how is this even legal?? I saw a documentary where one of the survivors said they couldn’t hug their own kids because their arms were too short… and now it’s being prescribed like it’s a vitamin?? 🤯 #ThalidomideIsNotAFashionStatement #NeverAgain

Husain Atther

January 24, 2026 AT 21:59The historical significance of this case cannot be overstated. It represents a pivotal moment in the evolution of pharmacovigilance and regulatory science. The diligence of Dr. Kelsey exemplifies the critical importance of scientific integrity over commercial pressure. While the human cost was catastrophic, the institutional reforms that followed have safeguarded countless future generations. This is not merely a medical history lesson-it is a moral imperative for modern clinical practice.

Helen Leite

January 25, 2026 AT 05:27WAIT WAIT WAIT. Did you know the government knew about this and STILL let it happen?? 😳 I read somewhere that Big Pharma paid off the FDA and the CIA was involved in testing it on soldiers!! 🧪👽 They’re probably still hiding other drugs like this… I bet 5G is next. 📶👶 #CoverUp #ThalidomideWasAExperiment

Sushrita Chakraborty

January 27, 2026 AT 03:09It is, without question, one of the most profound tragedies in the annals of pharmaceutical history. The failure to recognize species-specific metabolic pathways underscores a fundamental oversight in early toxicological assessment. Furthermore, the delayed recognition of peripheral neuropathy as a precursor to teratogenicity reveals a troubling disconnect between clinical observation and scientific inquiry. The subsequent regulatory reforms, while necessary, arrived at an unacceptable cost.

Josh McEvoy

January 29, 2026 AT 00:05bro i just took some melatonin last night and now i’m paranoid i’m gonna have a baby with no arms 😅 what if my dog’s flea meds are worse than thalidomide?? 🐶💊 #dontjudgemeimjustaworriedperson

Sawyer Vitela

January 29, 2026 AT 01:18Thalidomide’s mechanism is cereblon binding. Teratogenicity is dose-dependent and window-specific. No safe threshold. FDA’s STEPS program works. Alternatives exist. Stop dramatizing. Facts matter.

Vatsal Patel

January 29, 2026 AT 18:24Ah yes, the great irony: a drug that kills embryos is now hailed as a miracle cancer cure. How poetic. We glorify the healer while burying the victims. We call it 'progress' when it's just convenience wearing a lab coat. The real tragedy isn't the birth defects-it's that we still trust pills more than we trust our own caution.

Sharon Biggins

January 30, 2026 AT 16:13thank you for writing this. i’m pregnant and i was so scared after reading this but now i know to ask my doctor about every med-even the 'harmless' ones. you’re helping people. 💙